Her canine's life on the line, Army veteran turns to the Gary Sinise Foundation and Texas A&M

Harley was loyal until the day he died.

“He was always there for me,” Kerri Horan-Garza said of the omnipresent Golden Retriever. “When things had gotten very, very hard in my life, he knew just how to crawl up and give me cuddles.”

Soulmates, they saved each other.

“I’ve had dogs growing up my whole life, and I’ve had dogs that I’ve very much loved my whole life. But Harley was a little different.”

In July 2009, Horan and her boyfriend drove to the local animal shelter in Lewisville, Texas, to adopt a Beagle — a surprise gift for her 23rd birthday. But as they visited with the dog, its hyperactive demeanor overwhelmed Horan, who thought they better look for an alternative.

Walking through the shelter amidst the cacophony of dogs barking, there was Harley, sitting quietly a few feet away from his gate, “gently wagging his tail and just kinda waiting to be noticed,” Horan remembers.

As they filled out the adoption paperwork, the animal control officer let slip that their adopted dog was one of several scheduled to be euthanized after closing. She told them, “You just saved his life.”

At the time, Horan was seven months removed from a combat deployment to Kuwait. Physically and psychologically, war had changed her. Though Horan saved Harley’s life, she said, “for the next eleven years, he saved my life many times.”

Not long into the 12-month deployment did Horan’s mundane, relatively safe job as a supply specialist quickly evolve after a team of Navy corpsmen was reassigned, leaving Army medics in her unit from the 411th Ambulance Company pulling double duty, “twenty-four on, twenty-four on call.”

“I wasn’t prepared for, by any means, the kind of medical emergencies that we sometimes got,” Horan said. From Camp Arifjan in Kuwait, her unit carried out missions into Iraq, oftentimes driving along the “Highway of Death,” where in 1991, during the Persian Gulf War, hundreds of fleeing Iraqi soldiers were killed by U.S. and coalition forces.

Not every mission was designated as a critical transport. But those missions that were critical she’s spent years trying to forget, like the day she witnessed a “horrific accident” involving a civilian contractor. “You never quite forget the smell of human brains frying on a highway.”

But the perilous roads in Iraq were just one of her worries. Her marriage was crumbling even before she left for the Persian Gulf — divorce was imminent. Hardly a moment passed when she wasn’t thinking about Brandon, her 18-month-old son.

Yet lurking beneath the surface was a pernicious feeling that was causing her stress and anxiety. It was the same feeling she had at Fort Hood before shipping out. “For me, my enemy wasn’t necessarily outside the wire. It was inside.”

In its fiscal year 2008 annual report to Congress on sexual assault in the military, the Department of Defense received 2,908 claims of sexual assault between Oct. 1, 2007, and Sept. 30, 2008. The Pentagon investigated 2,389 of those claims, including reports of sexual assault occurring in combat zones like Iraq, Afghanistan, and Kuwait. In the 2020 fiscal year report, DOD received 7,816 reports of sexual assault involving service members.

“The incidence of sexual assault on base was as high as one in four,” Horan recalls about the chronic problem at U.S. bases in Kuwait. She was never preyed upon during the deployment, but multiple rumors about female soldiers sexually assaulted at Camp Buehring, near the Iraqi border, left Horan with little choice: she lived on guard, in fear.

“It’s pretty terrifying to live every day of your life having to have someone there with you, someone to guard you,” she said, “because you could be assaulted at just about any point.”

“There’s no time that you truly feel safe.”

On Christmas Day, Horan received an email from her estranged husband explaining that he planned to return to Guatemala, his missionary roots, to live with family friends. He was bringing Brandon.

Horan consulted with a judge advocate general at Camp Arifjan, who put a hold on Brandon’s passport before her parents drove from their home nearby and retrieved the boy. By the time Horan arrived home in January, three months ahead of schedule, and obtained full custody of Brandon, there was momentary relief: She had left a war-torn country for one on the brink of financial collapse with no job waiting for her and little savings left in her bank account.

For the next four years, Horan felt utterly lonesome. It didn’t help that she was chronically exhausted and sick at unpredictable moments since returning from Kuwait. She was bedridden one day, then fine the next. Despite counseling she received at a Veterans Affairs clinic, her mind and body continued in this twisted paradigm for months, then years.

Horan’s breaking point came in the throes of a nasty divorce from her second husband. She convinced herself that her two children “would be better off without a broken mother.” (Horan gave birth to a daughter in 2011). “I was well and truly alone,” Horan remembers. “There was no support, nothing from anyone.” Bills weren’t paid on time, and she struggled to put enough food on the table for her and the children.

Depression set in. And it seemed that her career as a Texas realtor had plateaued. Suicidal thoughts came and went at a flurry.

In 2014 Horan was diagnosed with fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome — both attributed to Gulf War illness. According to the VA, the illness is common in veterans who served in Southwest Asia as far back as 1990. “My bright spot, the thing that helped me keep going,” Horan said, “was definitely Harley.”

Alone at home, she felt secure in his presence. When she needed comfort, Harley was there to cuddle with her. “When I needed to be loved the most, loved without anything else, any expectations...he was there.”

He was always there.

In 2019, the Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences in College Station established the Veterinary Valor Program. What began as an endowed fund in honor of Dimitri del Castillo, a West Point graduate and Army Ranger killed in Afghanistan in 2011, has grown to include additional funding partners like the Gary Sinise Foundation.

“Even before the funds were established, we knew there was such a great need for it,'' said Dr. Stacy Eckman, associate dean for hospital operations at the Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital.

The program assists service members, veterans, and first responders defray all or portions of medical costs for their animal with care delivered at the school’s Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital. Said Eckman, “To think of people who truly put their lives in harm's way for all of us, this was just a small thing we can do.”

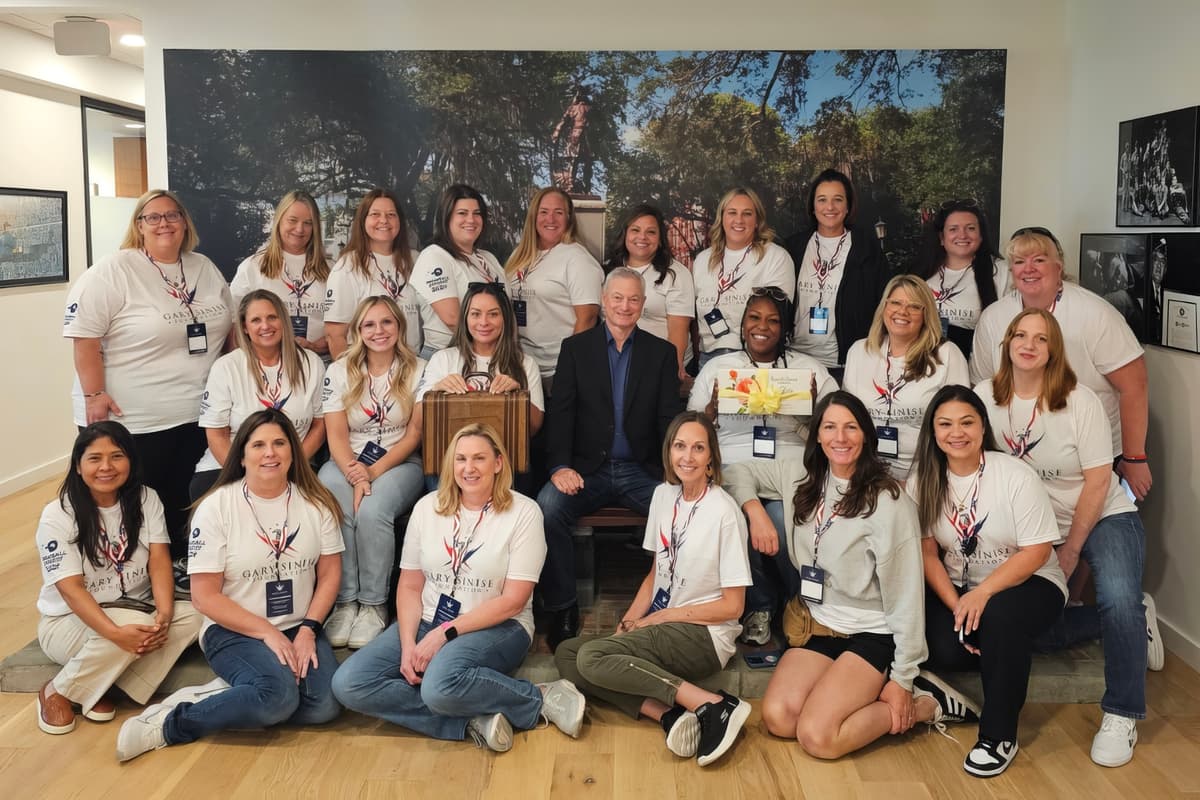

Last Nov., the Gary Sinise Foundation and the teaching hospital established the Veterinary Valor Fund. Like the valor program, the valor fund covers medical costs of animals owned by veterans and first responders. The partnership comes as the foundation expands its mental health services.

“Everybody’s got needs, but this is a group of people who have clearly already paid it forward,” Eckman said, “and the least we can do is help them with their companions.” Already, the valor fund has covered 73 families afford more than $87,000-worth in veterinary care.

Even at 11 years old, the way Harley was limping last Oct. seemed out of character. Alarmed by his behavior, Horan brought him to her veterinarian, who delivered a heart-wrenching conclusion after looking over his X-rays: Harley had bone cancer. His time was limited.

A month later, after doctors at the teaching hospital amputated one of Harley’s legs, he developed a secondary infection. Despite their best efforts, Harley's cancer metastasized to other parts of his body. So too did the infection. When he later slipped a disk along his spine, doctors informed Horan that his recovery was out of the question — Harley was out of time.

In the waning hours of Harley’s life, Horan was at his side; her scarf wrapped around him “because it smelled like mamma.” She held him like a child as he drew his final breath.

“I fought the hardest fight that I could’ve fought,” Horan said. “Because of this foundation [Gary Sinise Foundation], I was able to say, ‘Yes,’ to every test, every surgery, everything that was needed because I was able to receive the funds that I needed. Cost wasn’t a big concern.”

“I was able to fight for him as hard as he deserved.”

In July, nearly 12 years to the day she had rescued Harley, a breeder in Oklahoma called Horan, asking if she might be interested in adopting a two-year-old Golden Retriever named Moses. Horan thought it was fate and drove from her home in Dallas to Oklahoma City, where she and Quinn, the family’s Great Pyrenees mix, met the breeder and Moses.

The dogs played and took turns sniffing the other while Horan sat nearby watching the frolic. Mo, as he’s called, then broke away from Quinn and crawled into Horan’s lap. Like Harley, Mo hasn’t left her side.